Beyond Numbers: Navigating Valuation, Psychology, Biases and Missed Opportunities

Are you able to hold multibaggers even if they exceed their intrinsic value?

In one of my earlier posts in September 2022, discussing Reply (Ticker: REY), I touched upon a significant shift in my investment approach: moving away from traditional valuation methods like Discounted Cash Flow (DCF), or at least placing less emphasis on it as I continue going further in analysing companies and businesses.

After ample reflection and some research, I believe I have gathered enough insights to share my perspectives on valuation and how biases impact investment strategies.

Before we dive into it, here is one of my favourites and Charlie Munger classics about valuation 👇

As an engineer with a strong affinity for mathematics, I initially found great joy in the ups and downs of calculating and predicting a company’s intrinsic value.

I read books on valuation, pored over research papers, and consumed countless YouTube videos and podcasts. Yet, when the moment of truth arrived—when shares of a company, whose intrinsic value I had passionately calculated, dropped below my estimated number—I often found myself hesitating to pull the trigger on the buy.

But why? What happened ?

In short, the future is a riddle wrapped in an enigma. But, let's first quickly go over how to calculate the intrinsic value, explore why it's more art than science, and understand why sometimes, the numbers just don't add up.

The Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) and Flawed Assumptions

The following DCF formula, as explained by Investopedia, shows the mathematics involved in the process of calculating a company's intrinsic value.

In a nutshell, DCF is a valuation method used to estimate the present value of a company or investment based on its expected future cash flows. It involves forecasting a company's free cash flows and discounting them to their present value.

So, in order to determine intrinsic value using DCF, two major assumptions are required:

projecting future cash flows (CF) over a period like 5 or 10 years, and then

calculating the discounted rate (r), often using the Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC).

This part of the process is quite interesting because it involves figuring out how fast the money coming in will grow and how much it costs to get that money. It becomes even more challenging when dealing with early-stage or rapidly growing companies because it's like trying to predict the future using a financial crystal ball, filled with numerous possibilities but difficult-to-forecast changes.

I suppose some will appropriately quote John Maynard Keynes here:

“It is better to be roughly right than precisely wrong.”

However, the point I want to make here is not about questioning the effectiveness or functioning of the DCF method itself, but rather about how the results impact an investor. As mentioned above, DCF calculations are heavily influenced by the assumptions made, and it's vital to assess whether investors are emotionally ready to digest the end results. So, the following two questions frequently arise, especially considering market volatility:

Are you emotionally ready to make a purchase if the shares fall below the intrinsic value you calculated?

What are you going to do if the share price reaches the calculated intrinsic value?

I want to leave you with these questions for a moment, provide a few examples, and share my thoughts afterwards.

Market Sentiment and Missed Opportunities

Meta

Flashback to October 2022 - Meta's shares plunged below $100, an apparent bargain according to many financial models. Yet, many investors, myself included, were reluctant to act. Even it screamed as a golden opportunity, right?

Please share your feedback, I’m curious about your thoughts 👇

Constellation Software

Or, take Constellation Software, the Canadian software giant. Since its 2006 IPO, its shares have 🚀, yielding a return of over 18,000%!

And, how many of us regret selling Constellation Software too early when it reached its “intrinsic value” ?

Or, can we truly estimate how Mark Leonard, the founder and CEO of Constellation Software, and one of the best capital allocators, will perform in the future, especially in terms of managing and generating cash flows?

Investing and Our Brain: Managing the Emotional Fireworks (If Possible at All)

“The most important quality for an investor is temperament, not intellect.” – Warren Buffet

According to JP Morgan's quarterly "Guide to the Markets" report, the 20-year annualized returns for various asset classes from 2002 to 2021 show that the average investor achieved an annual return of only 3.6%, whereas the S&P 500 delivered a 9.5% return.

From my current reading of "Your Money and your Brain" by Jason Zweig, I learned that in the field of behavioral economics, several studies have clearly demonstrated that investors tend to make decisions not based on logical reasoning, but rather driven by emotions such as fear, greed, overconfidence, and various other irrational biases.

Unfortunately, this irrational behaviour can hurt how much money the average investor makes in investing.

Cognitive Errors: Their Impact on Our Investments

When I began my journey into investing, I had some basic knowledge about how our brain functions. This understanding stemmed from several years of delving into Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML), which, in essence, attempt to mimics our human brain (although I must admit that this explanation is oversimplified). My interest in Neuroscience, study of how the nervous system works, including our brain, also grew by time, leading me to explore books like Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahnemann.

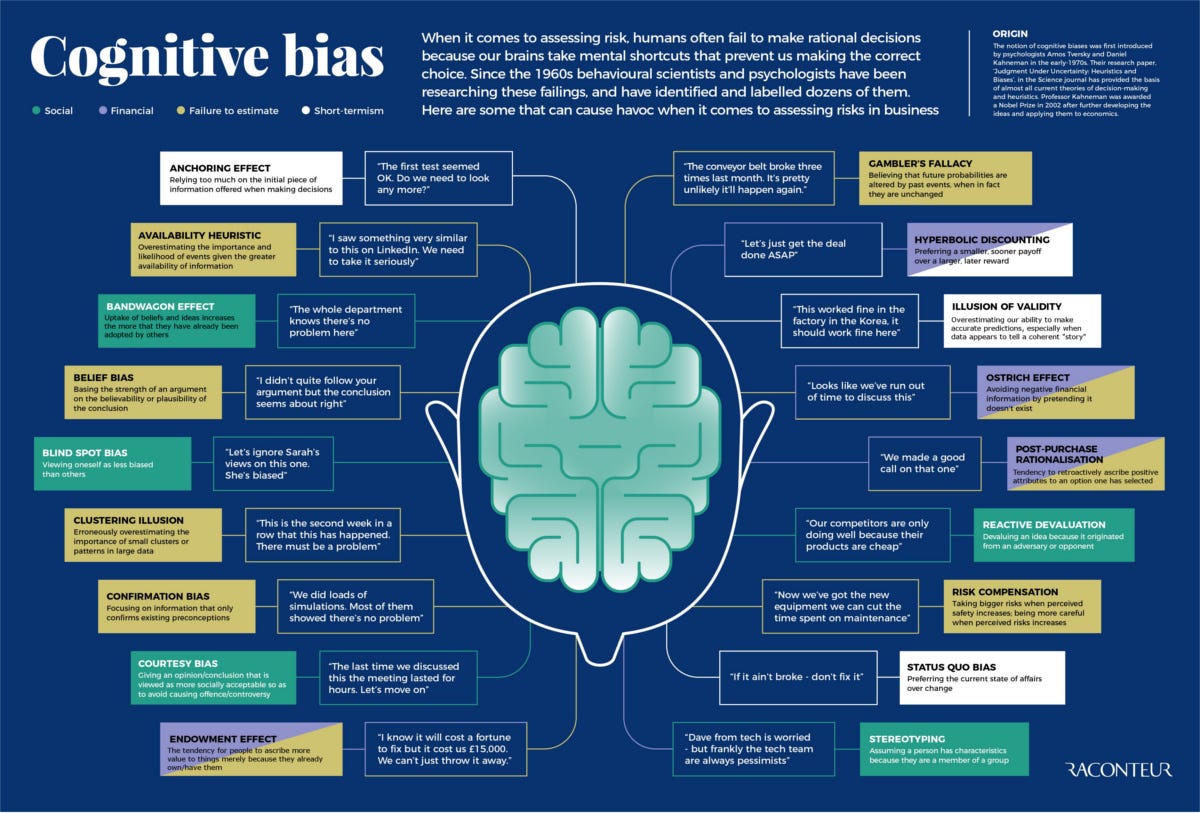

This was the first time I became aware with the concept of Cognitive Biases, which are basically systematic errors in our thinking that affect the decisions and judgments we make as we process and interpret information in the world around us.

And, here, when it comes to biases in the context of finance and investing, there is another Charlie Munger classic, absolutely worth studying.

Charlie Munger's investment philosophy is closely tied to principles of behavioural finance, emphasising the importance of understanding cognitive and emotional factors that influence decisions. He highlights the need to recognize and control biases, to make more rational investment decisions.

Let's briefly touch upon and become aware of a few common biases that influence investors' behaviour and ultimately affect performance in the end.

Confirmation Bias:

This is the tendency to favor information that confirms our existing beliefs. For example, if you believe a certain stock is a good buy, you're more likely to pay attention to positive news about the company and ignore negative reports.Overconfidence Bias:

Many investors overestimate their ability to predict market movements. This can lead to risky decisions, such as putting too much money in a single investment, thinking it's a sure win.Herd Mentality:

This bias occurs when investors follow what everyone else is doing rather than making their own independent analysis. A classic example is the dot-com bubble, where investors rushed into internet stocks simply because everyone else was, regardless of valuations.Anchoring Bias:

Refers to the human tendency of relying too much on a piece of information when making decisions. For example, if an investor buys a stock at $100 and it drops to $80, they may still perceive $100 as the stock's true value, ignoring market trends and updated analysis that suggest a different valuation.

Investing, as it turns out, is not just a game of numbers. Understanding and navigating the emotions and biases involved is as crucial as the financial analysis itself. From overconfidence to anchoring, these biases can cloud our judgment and lead us away from logical decisions, putting us on an emotional roller coaster.

Based on my personal experiences, although I don't have scientific evidence to support this, I've observed that the anchoring bias has a distinct impact on investors, especially when they're calculating intrinsic values. It affects decisions not only when stocks dip below their intrinsic value but also leads investors to sell prematurely because they tend to stick to their initial intrinsic value calculations.

Final Thoughts

I often try to remind myself of basic investment principles, such as the philosophy of Terry Smith, one of the UK's most popular money managers.

Find Great Companies

Don’t Overpay

Do Nothing

As I personally don't struggle with the first two principles, I train myself in the third, which, I believe, becomes easier without putting too much emphasis on the price tag as a result of intrinsic value calculation, thus preventing anchoring to a specific price every time the market fluctuates.

It's possible that I might reverse my stance on DCF and similar valuation methods in the future. For now, though, I feel comfortable using basic historical and relative earnings multiples. I'm focusing more on the business environment, industry dynamics, and understanding the sustainability of a business's competitive advantage while I'm doing my research.

Stay curious, stay informed, and most importantly, stay true to your investment goals!

Disclaimer: This publication and its authors are not licensed investment professionals. The information provided in this publication is for educational purposes only and should not be construed as investment advice. We do not make any recommendations regarding the suitability of particular investments. Before making any investment decision, it is important to do your own research. RhinoInsight assume no liability for any investment decisions made based on the information provided in this newsletter.

Reference:

Cognitive Biases

https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-a-cognitive-bias-2794963Exploring Charlie Munger’s Views On Behavioral Finance

https://pictureperfectportfolios.com/exploring-charlie-mungers-views-on-behavioral-finance/

great take, cheers!

Thanks Maverick🙏👍